Gary A Mauser, Ph.D recently made this submission to the Federal Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security on Bill C-71. He provides a great deal of analytical and factual analysis of the bill and calls it a Red Herring. Gary is a leading expert on the state of gun control and firearms law in Canada and has spent decades focusing his research in this area. The full submission is below.

Submission

April 2018

Gary A Mauser, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus

Institute for Canadian Urban Research Studies

Beedie School of Business

Simon Fraser University

Thank you for this opportunity to present my observations to the Committee on Bill C-71, “An Act to amend certain Acts and Regulations in relation to firearms.”

I am concerned that Bill C-71 is founded on faulty assumptions. Assumptions that ignore the real problem of violent gang crime to focus exclusively – and unnecessarily — on law-abiding firearms owners — hunters, sport shooters, and firearms retailers — individuals who do not pose a threat to public safety. The problem is violent crime, not firearms ownership.

There are many egregious problems with Bill C-71. In essence, this bill is a red herring, intended to distract the Canadian public from the government’s failure to deal with gang violence. Here, I will content myself with briefly identifying a few errors in the underlying assumptions in the bill.

By selecting the year 2013 as the base of comparison, the government abuses statistics to argue shootings are increasing. The year 2013 is an outlier.

The year 2013 saw Canada’s lowest rate of criminal homicides in 50 years (1.45 per 100,000), and the lowest rate of fatal shootings ever recorded by Statistics Canada (0.38 per 100,000). Naturally, this results in 2016 (1.68 homicides and 0.61 fatal shootings per 100,000) being an increase from 2013.

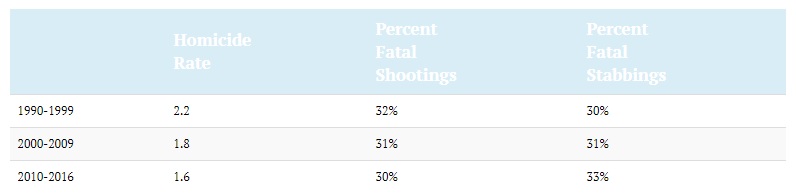

Total homicides have declined at least since the 1990s, not the “steady increase” the government claims. If anything, stabbings have steadily increased, not shootings.

Firearm homicides have declined from 32% in the 1990s to 30% of homicides since 2010, while stabbing homicides have increased from 30% in the 1990s to 33% since 2010.

Canada has a gang problem, not a gun problem. Criminal violence is driven by a small number of repeat offenders, not by the many Canadians who legally own firearms.

Statistics Canada reports that there were 223 firearms-related homicides in 2016; the bulk of the which (141 of the 223) were gang related. There are many instruments available to commit murder for those so inclined. Knives, clubs and fists suffice for many killers.

Licensed gun owners (Possession and Acquisition Licence holders) pose no threat to public safety. PAL holders had a homicide rate lower (0.60 per 100,000 licensed gun owners) than the national homicide rate (1.85 per 100,000 people the general population).

While Canada’s legal guns are more likely to be found outside of metropolitan areas, the vast bulk (121 of the 141) of gang related homicides involving firearms were committed in metropolitan areas in 2016, according to Statistics Canada.

Surveys find that 13% of households in urban areas report owning a firearm, while 30% in rural areas do so. Despite the lower legal gun density, gun crime is higher in urban Canada.

In urban Canada (defined as Census Metropolitan Areas), firearms are involved in 33% of homicides while outside of CMAs, firearms are involved in just 25% of homicides.[1]

Minister Goodale is correct in pointing out the higher rates of gun violence in some rural areas. Unfortunately, property crime, violent crime (including gun crimes) are quite high on First Nations Reserves, which predominate in rural Canada (among non-CMA’s with populations under 10,000). These problems are particularly acute in the Prairie Provinces.

There is no convincing empirical support for the assumption in Bill C-71 that tightening up restrictions on law-abiding firearms owners (PAL holders) will somehow restrict the flow of guns to violent criminals, and therefore, contribute to reducing gang violence.

Criminologists agree that no substantial evidence exists that legislation restricting access to firearms to the general public is effective in reducing criminal violence.[2]

Criminals are not getting their firearms from law-abiding Canadians, either by stealing them or through straw purchases. At the height of the long-gun registry, only 9% of firearms involved in homicides were registered (135 out of the 1,485 firearms homicide from 2003 to 2010), Statistics Canada revealed in a Special Request. To put this another way, just 3% of the 4,811 total homicides involved registered firearms during that time period.

All reputable research indicates that gang crime — urban or rural — is driven by smuggled firearms that flow to Canada as part of the illegal drug trade. Analyses of guns recovered from criminal activity in Toronto, Ottawa, Vancouver and the Prairie Provinces show that between two-thirds and 90% of these guns involved in violent crime had been smuggled into Canada.[3]

The claim that criminals get their guns from “domestic sources” is false and misleading. This claim cannot justify additional restrictions on firearms ownership and use by PAL holders.

The first problem with this claim is the unwarranted implication that the term “domestic sources” is synonymous with PAL holders. The authorities are embarrassed to admit there is a large pool of illegal firearms in Canada (and almost as many unlicensed gun owners as there are PAL holders).

When licensing was mandated in 2001, between one-third and one-half of then-law-abiding Canadian gun owners declined to apply for a PAL or POL.[4] Even though official estimates of civilian gun owners ranged from 3.3 million to over 4.5 million in 2001, fewer than 2 million licenses were issued.[5] As of 31 December 2016, the Canada Firearms Program reported there were 2,076,840 individual firearms licence holders.

Secondly, the claim that criminals get guns from “domestic sources” is based on an inflated definition of “criminals” and “crime guns.” Traditionally, “crime guns” are defined as guns used (or suspected of being used) in criminal violence, however, Canadian police have now considerably expanded the definition by including any gun “illegally acquired.”

The traditional definition of a “crime gun,” as illustrated by the 2007 Ontario Provincial Weapons Enforcement Unit (PWEU):

A “crime gun” is any firearm:

That is used, or has been used in a criminal offence;

That is obtained, possessed or intended to be used to facilitate criminal

activity;

That has a removed or obliterated serial number.[6]

This traditional definition of “crime gun” is identical to that continuously used by the FBI in the USand the British Home Office.

This new definition, in addition to guns used in violent crimes, now includes guns confiscated for any administrative violation (e.g., unsafe storage) as well as “found guns,” including guns recovered from homes of suicides (even when the suicide did not involve a firearm).

“A firearm is a crime gun if it meets any one of the following criteria:

“any firearm that is illegally acquired, suspected to have been used in

crime (includes found firearms),

has an obliterated serial number, or

has been illegally modified (e.g., barrel significantly shortened).”

(Page 10 of the 2014 FIESD Report).[7]

The term “found guns” is a “trash can” category. One semi-official description is:

“Found firearms not immediately linked to a criminal occurrence are referred to the Suspicious Firearms Index. Law enforcement officers may come into possession of firearms suspected of being associated with criminal activity, but which are not the subject of an active investigation. These typically include found and seized firearms where no charges are pending.” [8]

In sum, the claim that criminals get their guns from “domestic sources” is misleading and cannot justify additional restrictions on firearms ownership and use by PAL holders. Given the large pool of firearms held by unlicensed Canadians, it is unsurprising that guns seized by the police or surrendered to them are “domestically sourced.” But these are not guns used to commit violent crimes; those are predominantly smuggled.

Bill C-71 is unnecessary and does not contribute to public safety. Canadian gun laws are already enormously complex and constitute a maze for unwary firearms owners. Since 1998, gun crime is predominantly administrative violations not violent crimes.

In 2012 Statistics Canada reported that there were 12,320 administrative firearms violations in Canada (outside Quebec) compared with 5,575 “firearm-related” violent crimes [9] or the 1,325 crimes where a firearm was used to injure a victim.

The final total of administrative violations for Canada is somewhat higher than 12,320 because information from Quebec was excluded from this count due to Statistics Canada’s concerns over statistical irregularities in Quebec reports. [See Text box 5].

According to a special request to Statistics Canada, very few (4%) of these administrative crimes involved violence. [10] Almost all were merely paper crimes. In 96% of these cases, the gun owner in question was just charged with administrative violations, without involving any additional charges for violent crimes.

Summary and conclusions

By conflating gang violence with gun violence, Bill C-71 breaks the government’s repeated promises that criminal legislation will rely upon “evidence-based decision making.” Bill C-71 exaggerates the problem with guns by relying upon false assumptions to target law-abiding citizens instead of criminals.

Bill C-71 is a red herring. The real problem, ignored in this bill, is gang violence. Bill C-71 focuses on PAL holders, not violent criminals. Hunters and sport shooters are not the problem. Legal guns are not a major conduit for criminals to get guns. The public is not at risk from law-abiding PAL holders.

The additional regulatory complexity created by Bill C-71 will increase demands upon government services and increase costs to taxpayers. This can only reduce public safety.

The problem is violent crime, not ‘gun crime.’ When will the government get serious about gang violence?

Footnotes

[1] Professor Gary Mauser, Special Request, Statistics Canada, 2017. Number, CRO0163028.

[2] Baker, J. and S. McPhedran. 2007. Gun Laws and Sudden Death: Did the Australian Firearms Legislation of 1996 Make a Difference? British J. Criminology. 47, 455–469; Kates, Don B., and Gary Mauser. 2007. Would Banning Firearms Reduce Murder and Suicide? A Review of International Evidence. Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy 30, 2 (Spring): 649–94; Kleck, Gary (1997). Targeting Guns: Firearms and Their Control. Aldine de Gruyter; Langmann, Caillin. Canadian Firearms Legislation and Effects on Homicide 1974 to 2008, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2012, 27(12) 2303–2321; Mauser, Gary and Richard Holmes. An Evaluation of the 1977 Canadian Firearms Legislation, Evaluation Review, 1992 16: 603; Mauser, Gary and Dennis Maki, An evaluation of the 1977 Canadian firearm legislation: robbery involving a firearm; Applied Economics, 2003, 35:4, 423-436; National Research Council of the National Academies, Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review 7;m (2004), available at http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10881&page=7:

[3] Cook, Philip, W Cukier and K Krause, “ The illicit Firearms Trade in North America,“ Criminology and Criminal Justice. Vol 9(3), 2009, 265-286. Toronto Mayor Tory told the Guns and Gangs summit meeting (7 March 2018) that at least 50% of the guns used in homicide had been smuggled, and that just 2% had no connection to the drug trade. Gary Mauser, “Will Gun Control Make Us Safe? Debunking the Myths. An evaluation of firearm laws in Canada and in the English Commonwealth,” invited address to the Ontario Police College, Toronto, Ontario, May 24-25, 2006.

[4] Professor Gary Mauser. The Case of the Missing Canadian Gun Owners. Presented to the annual meeting of the American Society of Criminology, Atlanta, Georgia, November 2001.

[5] MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT RESPECTING THE FEDERAL- PROVINCIAL FINANCIAL AGREEMENT ADDRESSING THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE FIREARMS ACT AND REGULATIONS. March 29, 1999.

[6] Minutes of the Toronto Police Services Board, January 22, 2004.

[7] Professor Gary Mauser and Dennis Young. Critique of the RCMP’s Firearms and Investigative Services Directorate (FIESD) 2014 Annual Report. The definition is on page 10 of the FIESD report.

[8] Heemskirk, Tony and Eric Davies. A report on illegal movement of firearms in British Columbia. PSSG-09-003. 2009 http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/law-crime-and-justice/criminal- justice/police/publications/independent/special-report-illegal-movement-firearms.pdf

[9] A firearm need not be used in a crime for Statistics Canada to considers a crime “firearms-related.” A crime is “firearms-related” if a firearm the “most serious weapon present” during the commission of the crime (or is later found at the scene).

[10] Professor Gary Mauser, Statistics Canada Special Request number 85C9996, 17 May 2017.