In an interview given by the Minister of Public Safety Ralph Goodale to the CBC and published March 20, 2018, the Minister said this about the new, detailed transaction records required to be maintained by retail vendors of firearms regarding their sales:

“… it’s simply not a federal long gun registry, full stop, period. The requirement for retailers to maintain their own private record is just that, they’re private records of the retailers, and they will not be accessible to government. They would be accessible to police when they are investigating gun crimes, with the proper basis of reasonable cause and judicial authorization through a warrant. That’s how the police investigate private information now in any event with respect to every other manner of events…”

http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/liberals-firearms-bill-c71-1.4584074

This is simply not true.

The Firearms Act creates a very clear system for the government to easily access all of the records maintained by a firearms business, in a section of the Firearms Act appropriately titled “Inspection”. They simply need to send in an Inspector under the following provisions of the Firearms Act:

Inspection

Definition of “inspector”

101 In sections 102 to 105, inspector means a firearms officer and includes, in respect of a province, a member of a class of individuals designated by the provincial minister.

Inspection

102 (1) Subject to section 104, for the purpose of ensuring compliance with this Act and the regulations, an inspector may at any reasonable time enter and inspect any place where the inspector believes on reasonable grounds a business is being carried on or there is a record of a business, any place in which the inspector believes on reasonable grounds there is a gun collection or a record in relation to a gun collection or any place in which the inspector believes on reasonable grounds there is a prohibited firearm or there are more than 10 firearms and may

(a) open any container that the inspector believes on reasonable grounds contains a firearm or other thing in respect of which this Act or the regulations apply;

(b) examine any firearm and examine any other thing that the inspector finds and take samples of it;

(c) conduct any tests or analyses or take any measurements; and

(d) require any person to produce for examination or copying any records, books of account or other documents that the inspector believes on reasonable grounds contain information that is relevant to the enforcement of this Act or the regulations.

Operation of data processing systems and copying equipment

(2) In carrying out an inspection of a place under subsection (1), an inspector may

(a) use or cause to be used any data processing system at the place to examine any data contained in or available to the system;

(b) reproduce any record or cause it to be reproduced from the data in the form of a print-out or other intelligible output and remove the print-out or other output for examination or copying; and

(c) use or cause to be used any copying equipment at the place to make copies of any record, book of account or other document. …”

In case you are wondering who a “firearms officer” is, that is provided by section 2(1) of the Firearms Act:

“Definitions

2 (1) In this Act, …

firearms officer means

(a) in respect of a province, an individual who is designated in writing as a firearms officer for the province by the provincial minister of that province,

(b) in respect of a territory, an individual who is designated in writing as a firearms officer for the territory by the federal Minister, or

(c) in respect of any matter for which there is no firearms officer under paragraph (a) or (b), an individual who is designated in writing as a firearms officer for the matter by the federal Minister; …”

Quite obviously under these provisions, it is not the case that the government requires a warrant or reasonable cause or any judicial oversight at all in order to enter into the premises of a firearm retailer, and examine and take copies of all of their books, documents or computer records.

Gary A Mauser, Ph.D recently made this submission to the Federal Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security on Bill C-71. He provides a great deal of analytical and factual analysis of the bill and calls it a Red Herring. Gary is a leading expert on the state of gun control and firearms law in Canada and has spent decades focusing his research in this area. The full submission is below.

Submission

April 2018

Gary A Mauser, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus

Institute for Canadian Urban Research Studies

Beedie School of Business

Simon Fraser University

Thank you for this opportunity to present my observations to the Committee on Bill C-71, “An Act to amend certain Acts and Regulations in relation to firearms.”

I am concerned that Bill C-71 is founded on faulty assumptions. Assumptions that ignore the real problem of violent gang crime to focus exclusively – and unnecessarily — on law-abiding firearms owners — hunters, sport shooters, and firearms retailers — individuals who do not pose a threat to public safety. The problem is violent crime, not firearms ownership.

There are many egregious problems with Bill C-71. In essence, this bill is a red herring, intended to distract the Canadian public from the government’s failure to deal with gang violence. Here, I will content myself with briefly identifying a few errors in the underlying assumptions in the bill.

By selecting the year 2013 as the base of comparison, the government abuses statistics to argue shootings are increasing. The year 2013 is an outlier.

The year 2013 saw Canada’s lowest rate of criminal homicides in 50 years (1.45 per 100,000), and the lowest rate of fatal shootings ever recorded by Statistics Canada (0.38 per 100,000). Naturally, this results in 2016 (1.68 homicides and 0.61 fatal shootings per 100,000) being an increase from 2013.

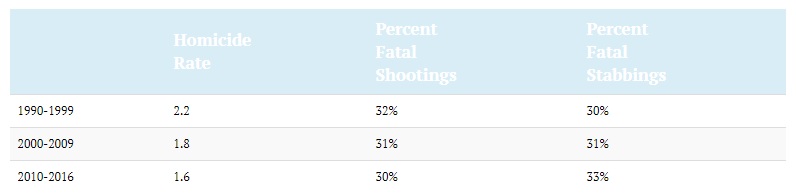

Total homicides have declined at least since the 1990s, not the “steady increase” the government claims. If anything, stabbings have steadily increased, not shootings.

Firearm homicides have declined from 32% in the 1990s to 30% of homicides since 2010, while stabbing homicides have increased from 30% in the 1990s to 33% since 2010.

Canada has a gang problem, not a gun problem. Criminal violence is driven by a small number of repeat offenders, not by the many Canadians who legally own firearms.

Statistics Canada reports that there were 223 firearms-related homicides in 2016; the bulk of the which (141 of the 223) were gang related. There are many instruments available to commit murder for those so inclined. Knives, clubs and fists suffice for many killers.

Licensed gun owners (Possession and Acquisition Licence holders) pose no threat to public safety. PAL holders had a homicide rate lower (0.60 per 100,000 licensed gun owners) than the national homicide rate (1.85 per 100,000 people the general population).

While Canada’s legal guns are more likely to be found outside of metropolitan areas, the vast bulk (121 of the 141) of gang related homicides involving firearms were committed in metropolitan areas in 2016, according to Statistics Canada.

Surveys find that 13% of households in urban areas report owning a firearm, while 30% in rural areas do so. Despite the lower legal gun density, gun crime is higher in urban Canada.

In urban Canada (defined as Census Metropolitan Areas), firearms are involved in 33% of homicides while outside of CMAs, firearms are involved in just 25% of homicides.[1]

Minister Goodale is correct in pointing out the higher rates of gun violence in some rural areas. Unfortunately, property crime, violent crime (including gun crimes) are quite high on First Nations Reserves, which predominate in rural Canada (among non-CMA’s with populations under 10,000). These problems are particularly acute in the Prairie Provinces.

There is no convincing empirical support for the assumption in Bill C-71 that tightening up restrictions on law-abiding firearms owners (PAL holders) will somehow restrict the flow of guns to violent criminals, and therefore, contribute to reducing gang violence.

Criminologists agree that no substantial evidence exists that legislation restricting access to firearms to the general public is effective in reducing criminal violence.[2]

Criminals are not getting their firearms from law-abiding Canadians, either by stealing them or through straw purchases. At the height of the long-gun registry, only 9% of firearms involved in homicides were registered (135 out of the 1,485 firearms homicide from 2003 to 2010), Statistics Canada revealed in a Special Request. To put this another way, just 3% of the 4,811 total homicides involved registered firearms during that time period.

All reputable research indicates that gang crime — urban or rural — is driven by smuggled firearms that flow to Canada as part of the illegal drug trade. Analyses of guns recovered from criminal activity in Toronto, Ottawa, Vancouver and the Prairie Provinces show that between two-thirds and 90% of these guns involved in violent crime had been smuggled into Canada.[3]

The claim that criminals get their guns from “domestic sources” is false and misleading. This claim cannot justify additional restrictions on firearms ownership and use by PAL holders.

The first problem with this claim is the unwarranted implication that the term “domestic sources” is synonymous with PAL holders. The authorities are embarrassed to admit there is a large pool of illegal firearms in Canada (and almost as many unlicensed gun owners as there are PAL holders).

When licensing was mandated in 2001, between one-third and one-half of then-law-abiding Canadian gun owners declined to apply for a PAL or POL.[4] Even though official estimates of civilian gun owners ranged from 3.3 million to over 4.5 million in 2001, fewer than 2 million licenses were issued.[5] As of 31 December 2016, the Canada Firearms Program reported there were 2,076,840 individual firearms licence holders.

Secondly, the claim that criminals get guns from “domestic sources” is based on an inflated definition of “criminals” and “crime guns.” Traditionally, “crime guns” are defined as guns used (or suspected of being used) in criminal violence, however, Canadian police have now considerably expanded the definition by including any gun “illegally acquired.”

The traditional definition of a “crime gun,” as illustrated by the 2007 Ontario Provincial Weapons Enforcement Unit (PWEU):

A “crime gun” is any firearm:

That is used, or has been used in a criminal offence;

That is obtained, possessed or intended to be used to facilitate criminal

activity;

That has a removed or obliterated serial number.[6]

This traditional definition of “crime gun” is identical to that continuously used by the FBI in the USand the British Home Office.

This new definition, in addition to guns used in violent crimes, now includes guns confiscated for any administrative violation (e.g., unsafe storage) as well as “found guns,” including guns recovered from homes of suicides (even when the suicide did not involve a firearm).

“A firearm is a crime gun if it meets any one of the following criteria:

“any firearm that is illegally acquired, suspected to have been used in

crime (includes found firearms),

has an obliterated serial number, or

has been illegally modified (e.g., barrel significantly shortened).”

(Page 10 of the 2014 FIESD Report).[7]

The term “found guns” is a “trash can” category. One semi-official description is:

“Found firearms not immediately linked to a criminal occurrence are referred to the Suspicious Firearms Index. Law enforcement officers may come into possession of firearms suspected of being associated with criminal activity, but which are not the subject of an active investigation. These typically include found and seized firearms where no charges are pending.” [8]

In sum, the claim that criminals get their guns from “domestic sources” is misleading and cannot justify additional restrictions on firearms ownership and use by PAL holders. Given the large pool of firearms held by unlicensed Canadians, it is unsurprising that guns seized by the police or surrendered to them are “domestically sourced.” But these are not guns used to commit violent crimes; those are predominantly smuggled.

Bill C-71 is unnecessary and does not contribute to public safety. Canadian gun laws are already enormously complex and constitute a maze for unwary firearms owners. Since 1998, gun crime is predominantly administrative violations not violent crimes.

In 2012 Statistics Canada reported that there were 12,320 administrative firearms violations in Canada (outside Quebec) compared with 5,575 “firearm-related” violent crimes [9] or the 1,325 crimes where a firearm was used to injure a victim.

The final total of administrative violations for Canada is somewhat higher than 12,320 because information from Quebec was excluded from this count due to Statistics Canada’s concerns over statistical irregularities in Quebec reports. [See Text box 5].

According to a special request to Statistics Canada, very few (4%) of these administrative crimes involved violence. [10] Almost all were merely paper crimes. In 96% of these cases, the gun owner in question was just charged with administrative violations, without involving any additional charges for violent crimes.

Summary and conclusions

By conflating gang violence with gun violence, Bill C-71 breaks the government’s repeated promises that criminal legislation will rely upon “evidence-based decision making.” Bill C-71 exaggerates the problem with guns by relying upon false assumptions to target law-abiding citizens instead of criminals.

Bill C-71 is a red herring. The real problem, ignored in this bill, is gang violence. Bill C-71 focuses on PAL holders, not violent criminals. Hunters and sport shooters are not the problem. Legal guns are not a major conduit for criminals to get guns. The public is not at risk from law-abiding PAL holders.

The additional regulatory complexity created by Bill C-71 will increase demands upon government services and increase costs to taxpayers. This can only reduce public safety.

The problem is violent crime, not ‘gun crime.’ When will the government get serious about gang violence?

Footnotes

[1] Professor Gary Mauser, Special Request, Statistics Canada, 2017. Number, CRO0163028.

[2] Baker, J. and S. McPhedran. 2007. Gun Laws and Sudden Death: Did the Australian Firearms Legislation of 1996 Make a Difference? British J. Criminology. 47, 455–469; Kates, Don B., and Gary Mauser. 2007. Would Banning Firearms Reduce Murder and Suicide? A Review of International Evidence. Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy 30, 2 (Spring): 649–94; Kleck, Gary (1997). Targeting Guns: Firearms and Their Control. Aldine de Gruyter; Langmann, Caillin. Canadian Firearms Legislation and Effects on Homicide 1974 to 2008, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2012, 27(12) 2303–2321; Mauser, Gary and Richard Holmes. An Evaluation of the 1977 Canadian Firearms Legislation, Evaluation Review, 1992 16: 603; Mauser, Gary and Dennis Maki, An evaluation of the 1977 Canadian firearm legislation: robbery involving a firearm; Applied Economics, 2003, 35:4, 423-436; National Research Council of the National Academies, Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review 7;m (2004), available at http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10881&page=7:

[3] Cook, Philip, W Cukier and K Krause, “ The illicit Firearms Trade in North America,“ Criminology and Criminal Justice. Vol 9(3), 2009, 265-286. Toronto Mayor Tory told the Guns and Gangs summit meeting (7 March 2018) that at least 50% of the guns used in homicide had been smuggled, and that just 2% had no connection to the drug trade. Gary Mauser, “Will Gun Control Make Us Safe? Debunking the Myths. An evaluation of firearm laws in Canada and in the English Commonwealth,” invited address to the Ontario Police College, Toronto, Ontario, May 24-25, 2006.

[4] Professor Gary Mauser. The Case of the Missing Canadian Gun Owners. Presented to the annual meeting of the American Society of Criminology, Atlanta, Georgia, November 2001.

[5] MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT RESPECTING THE FEDERAL- PROVINCIAL FINANCIAL AGREEMENT ADDRESSING THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE FIREARMS ACT AND REGULATIONS. March 29, 1999.

[6] Minutes of the Toronto Police Services Board, January 22, 2004.

[7] Professor Gary Mauser and Dennis Young. Critique of the RCMP’s Firearms and Investigative Services Directorate (FIESD) 2014 Annual Report. The definition is on page 10 of the FIESD report.

[8] Heemskirk, Tony and Eric Davies. A report on illegal movement of firearms in British Columbia. PSSG-09-003. 2009 http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/law-crime-and-justice/criminal- justice/police/publications/independent/special-report-illegal-movement-firearms.pdf

[9] A firearm need not be used in a crime for Statistics Canada to considers a crime “firearms-related.” A crime is “firearms-related” if a firearm the “most serious weapon present” during the commission of the crime (or is later found at the scene).

[10] Professor Gary Mauser, Statistics Canada Special Request number 85C9996, 17 May 2017.

In this video. Rod Giltaca discusses the realities of the restricted firearm registry in Canada.

Some examples of confiscation of firearms in Canada:

2010 - RCMP gun confiscations prompt legal fight

2007 – Feds budget $260,000 to seize rifles

1995 – 553,000 registered handguns become prohibited

What was the cost of the Long Gun Registry?

The modern Canadian long gun registry was over $2 Billion by the time it was scrapped by the previous government. CBC covered the story here: Gun registry cost soars to $2 billion

History of Canada's gun registry

1892

The first Criminal Code required individuals to have a basic permit, known as a 'certificate of exemption,' to carry a pistol unless the owner had cause to fear assault or injury. It became an offence to sell a pistol to anyone under 16. Vendors who sold pistols or airguns had to keep a record of the purchaser's name, the date of the sale and information that could identify the gun.

1913

Carrying a handgun outside the home or place of business without a permit could result in a three-month sentence. It became an offence to transfer a firearm to any person under the age of 16, or for a person under 16 to buy one. The first specific search, seizure and forfeiture powers for firearms and other weapons were created.

1919-1920

A Criminal Code amendment required individuals to obtain a permit to possess a firearm, regardless of where the firearm was kept. These permits were available from a magistrate, a chief of police or the RCMP. British subjects did not need a permit for shotguns or rifles they already owned; they only needed one for newly acquired firearms. Permits were valid for one year within the issuing province. The Criminal Code did not provide for a central registry; records were maintained at the local level.

1921

A Criminal Code amendment repealed the requirement for everyone in possession of a firearm to have a permit. Instead, only 'aliens' needed a permit to possess firearms. (British subjects still needed a permit to carry pistols or handguns).

1932-1933

Specific requirements were added for issuing handgun permits. Before this, applicants only had to be of 'discretion and good character.' They now also had to give reasons for wanting a handgun. Permits could only be issued to protect life or property, or for using a firearm at an approved shooting club. The minimum age for possessing firearms was lowered from 16 to 12 years. Other changes included the creation of the first mandatory minimum consecutive sentence - 2 years for the possession of a handgun or concealable firearm while committing an offence. The punishment for carrying a handgun outside the home or place of business was increased from 3 months to a maximum of 5 years.

1934

The first real registration requirement for handguns was created. Before then, when a permit holder bought a handgun, the person who issued the permit was notified. The new provisions required records identifying the owner, the owner's address and the firearm. These records were not centralized. Registration certificates were issued and records were kept by the Commissioner of the RCMP or by police departments that provincial Attorneys General had designated as firearms registries.

1938

Handguns had to be re-registered every five years, starting in 1939. (Initially, certificates had been valid indefinitely). While guns did not require serial numbers, it became an offence to alter or deface numbers (S.C.1938, c.44). The mandatory 2-year minimum sentence provision was extended to include the possession of any type of firearm, not just handguns and concealable firearms, while committing an offence. The minimum age was raised from 12 to 14 years. The first 'minor's permit' was created to allow persons under 14 to have access to firearms.

1939-1944

Re-registration was postponed because of World War II. During the war years, rifles and shotguns had to be registered. This was discontinued after the war ended.

1950

The Criminal Code was amended so that firearm owners no longer had to renew registration certificates. Certificates became valid indefinitely.

1951

The registry system for handguns was centralized under the Commissioner of the RCMP for the first time. Automatic firearms were added to the category of firearms that had to be registered. These firearms now had to have serial numbers. The 2-year mandatory minimum sentence created in 1932-33 was repealed after a 1949 Supreme Court decision ( R. v. Quon) found that it did not apply to common crimes such as armed robbery.

1968-1969

The categories of 'firearm,' 'restricted weapon' and 'prohibited weapon' were created for the first time. This ended confusion over specific types of weapons and allowed the creation of specific legislative controls for each of the new categories. The new definitions included powers to designate weapons to be prohibited or restricted by Order- in-Council. The minimum age to get a minor's permit to possess firearms was increased to 16. For the first time, police had preventive powers to search for firearms and seize them if they had a warrant from a judge, and if they had reasonable grounds to believe that possession endangered the safety of the owner or any other person, even though no offence had been committed. The current registration system, requiring a separate registration certificate for each restricted weapon, took effect in 1969.

1977

Bill C-51 passed in the House of Commons. It then received Senate approval and Royal Assent on August 5. The two biggest changes included requirements for Firearms Acquisition Certificates (FACs) and requirements for Firearms and Ammunition Business Permits. And, for the first time, Chief Firearms Officer positions were introduced in the provinces. Fully automatic weapons became classified as prohibited firearms unless they had been registered as restricted weapons before January 1, 1978. Individuals could no longer carry a restricted weapon to protect property. Mandatory minimum sentences were re-introduced. This time, they were in the form of a 1-14 year consecutive sentence for the actual use (not mere possession) of a firearm to commit an indictable offence.

After the 1993 federal election, the new Government indicated its intention to proceed with further controls, including some form of licensing and registration system that would apply to all firearms and their owners. Provincial and Federal officials met several times between January and July to define issues relating to universal licensing and registration proposals.

Between August 1994 and February 1995, policy options were defined for a new firearms control scheme, and new legislation was drafted.

1995

Bill C-68 was introduced on February 14. Senate approval and Royal Assent were granted on December 5, 1995. Major changes included:

the creation of the Firearms Act, to take the administrative and regulatory aspects of the licensing and registration system out of the Criminal Code;

a new licensing system to replace the FAC system; licences required to possess and acquire firearms, and to buy ammunition;

registration of all firearms, including shotguns and rifles.

The Chief Firearms Officer was tasked with issuing firearm licences, and the Firearms Registrar, registration certificates. The Registrar is responsible, among other things, for registering firearms owned by individuals and businesses.

Provision was also made in the Firearms Act for the appointment of ten Chief Firearms Officers, that is, one for each province, with some provinces also including a territory. Chief Firearms Officers can be appointed by the provincial or the federal government. Be they appointed federally or provincially, Chief Firearms Officers are responsible for such things as issuing, renewing, and revoking Possession and Acquisition Licences.

1996

The Minister of Justice tabled proposed regulations on November 27. These dealt with such matters as:

all fees payable under the Firearms Act;

licensing requirements for firearms owners;

safe storage, display and transportation requirements for individuals and businesses;

authorizations to transport restricted or prohibited firearms;

authorizations to carry restricted firearms and prohibited handguns for limited purposes;

authorizations for businesses to import or export firearms;

conditions for transferring firearms from one owner to another;

record-keeping requirements for businesses;

adaptations for Aboriginal people.

1997

In October, the Minister of Justice tabled some amendments to the 1996 regulations. She also tabled additional regulations at that time, dealing with:

firearms registration certificates;

exportation and importation of firearms;

the operation of shooting clubs and shooting ranges;

gun shows;

special authority to possess; and

public agents.

1998

The Canadian Firearms Registry was transferred from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to the Department of Justice.

2001

As of January 1, 2001, Canadians needed a licence to possess and acquire firearms.

2003

As of January 1, 2003, individuals needed a valid licence and registration certificate for all firearms in their possession, including non-restricted rifles and shotguns. Firearms businesses also required a valid business licence and registration certificate for all firearms in their inventory.

The Canada Firearms Centre was transferred from the Department of Justice on April 14, 2003, and became an independent agency within the Solicitor General Portfolio.

On May 13, 2003, Bill C-10A, An Act to Amend the Criminal Code (Firearms) and the Firearms Act received Royal Assent. Statutory authority of all operations was consolidated under the Canadian Firearms Commissioner, who reported directly to the Solicitor General, now known as the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada.

A Commissioner of Firearms, who has overall responsibility for the administration of the program, was appointed.

2005

Some Bill C-10A regulations — those which improve service delivery, streamline processes and improve transparency and accountability — came into effect.

2006

Responsibility for the administration of the Firearms Act and the operation of the Canada Firearms Centre was transferred to the RCMP in May 2006. The Commissioner of the RCMP assumed the role of the Commissioner of Firearms.

2011

On October 25, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness introduced Bill C-19, An Act to amend the Criminal Code and the Firearms Act (Ending the Long-gun Registry Act).

2012

On April 5, Bill C-19, the Ending the Long-gun Registry Act, came into force. The bill amended the Criminal Codeand the Firearms Act to remove the requirement to register non-restricted firearms, ordered the destruction of existing registration records and allowed the transferor of a non-restricted firearm to obtain confirmation of the validity of a transferee's firearms acquisition licence prior to the transfer being finalized.

Shortly after, the Government of Quebec filed a court challenge to Bill C-19. Due to a series of court orders and undertakings in these proceedings, non-restricted firearms registration records for the province of Quebec were retained, and Quebec residents continued to register non-restricted firearms.

In October, all non-restricted firearms registration records, except for Quebec, were destroyed.

2015

On March 27, the Supreme Court of Canada dismissed Quebec's appeal challenging the constitutionality of the provisions of the Ending the Long Gun Registry Act requiring destruction of the non-restricted registration records, and refused to order the transfer of these records to the Province of Quebec. As a result, the Canadian Firearms Program stopped accepting and processing registration/transfer applications for non-restricted firearms from within the province of Quebec, and all electronic records identified as being related to the non-restricted firearms registration records in Quebec were deleted. It was later discovered that two copies were actually kept.

In this Video, Rod Giltaca discusses the need for education on the topic of Gun Control in Canada. We encourage you to browse the site and learn as much as you can. There is an incredible amount of factual information contained within Gundebate.ca to explore. Not completely convinced, look for more info at Statistics Canada, at the RCMP, and at peer reviewed Canadian studies on relevant issues. The information is out there for you to find, and a huge amount of it is already organized here to save you time.

Rod talks about the normal reaction to gang crime in Canada; the desire to ban guns.

5 million people in peaceful possession?

The 2015 Commissioner of Firearms Report lists the number of individual licenced gun owners in Canada at 2,026,011 individuals. The number 2.1 million quoted in the video is a projection based on a continuation of the historical increase since the last published data at the end of 2015.

The full report can be found here. 2015 Commissioner of Firearms Report

Dr. Gary A. Mauser is a Canadian criminologist and emeritus professor in the Beedie School of Business at Simon Fraser University. He has done extensive research into gun control and firearms law in Canada. The actual number of gun owners in Canada is impossible to know, however his best estimate of the number of Canadians in peaceful possession of firearms in Canada is approximately 3 million.

Politicians punish law abiding gun owners after criminal shootings?

In May 2015, after a gang shoot out in Hamilton Ontario, the mayor’s idea to fix the problem was to prohibit all gun ownership in the City, including otherwise lawful ownership. This is just one example, but unfortunately these types of solutions are regular talking points after gang violence in Canada.

Read the article here: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/hamilton/news/hamilton-should-ban-guns-mayor-says-1.3080848

Does the simple presence of guns including those owned by lawful owners cause more violence?

We encourage you to read this Canadian Study published in 2015.

Do Triggers Pull Fingers? A Look at the Criminal Misuse of Guns in Canada

The conclusions in this study include “It is irrational to conflate civilian firearm owners with violent criminals. Civilian firearm owners are not embryonic killers—they are exemplary middle class Canadians. Firearms ownership is compatible with and conducive to good citizenship, and, accordingly, Canadian firearms owners are found to contribute substantially to their communities as responsible, law-abiding citizens. Historically, armed civilians have played crucial leadership roles in their communities, including protecting their country from invasion.

The Canadian findings are consistent with international research. Homicide rates have not been found to be higher in countries with more firearms in civilian hands. Nor is there convincing empirical support for most of the gun control measures in Australia, Jamaica, Republic of Ireland, Europe, the United Kingdom or in the United States. In sum, the proposition that restricting general civilian access to firearms acts to reduce homicide rates cannot be empirically justified.”

In this Video, Rod talks about how strange it is that the AR-15 is “restricted” while so many other functionally similar rifles are non-restricted in Canada. He offers some thoughts on the topic.

In Canada, semi-automatic rifles that function like the AR-15 are, in general, “non-restricted”. The AR-15 however is “restricted” by name because the politicians of the day thought it looked scary. Since then, dozens and dozens of new models of similar firearms have hit the market, are non-restricted by Canadian regulations, and are safely owned by millions of Canadians.

In this video Rod discusses the Canadian movement to legalise silencers for gun owners.

For more in depth information on this topic, we urge you to visit: Sound Moderators Canada

Supporting Information for the Video:

Amount of Noise Reduction

Sound Moderators reduce the sound of a firearm enough to make it safe. Often, traditional hearing protection is still recommended in addition to a Sound Moderator.

This Study by the Health & Safety Laboratory in the UK published in 2004 looked at the noise levels encountered at various positions around both moderated and un-moderated firearms and made recommendations on hearing protection to stay safe.

Interestingly, the study found that while using un-moderated firearms, traditional hearing protectors which were predicted to provide adequate protection according to standardized methods, were found to be inadequate as they did not always reduce the peak exposure below 140dB.

It also found that Sound Moderators do NOT give any reduction to the noise of a bullet in flight and therefore gave little to no noise reduction forward of the firearm.

Read the whole study below:

assessment-of-firearm-moderators-short-report-uk-health-safety-labratory

Rarely Used in Crimes

Silencers are rarely used in crimes, according to a 10-year study published in 2007 by the Western Criminology Review in the United States. Researchers estimated silencers were involved in 30 to 40 of the 75,000 federal criminal cases filed each year. The study found only two federal cases over a 10 year period involving a silencer used in murders. To put this number in perspective, environment Canada estimates that 10 people per year are killed or injured by lighting strikes.

Read the whole study below:

Criminal Use of Silencers Study

Countries with a degree of legal use for Civilians

Our research found that the majority of G7 nations and many others have recognized the benefits of these devices. These countries include the United States, France, Germany, Great Britain, Denmark, Finland, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Italy, Poland. We are sure there are other counties in addition to the ones we've listed.

Benefits

Sound Moderators are prohibited in Austrailia, but when a University was asked to do a study and offer their opinion on the topic, the authors’ opinions were that the prohibition should be lifted. The study examines the many benefits associated with the use of these devices.

Edith Cowen University in Austrailia published their study in 2011 on the implications of allowing Sound Moderators for use on firearms for game and faral management. It was prepared for the Game Council of New South Wales. The studies conclusion is no surprise:

“It is the opinion of the report-panel that when the documented advantages of sound

moderators are compared against a perceived amount of crime that criminalisation of the

device purports to prevent, then it is argued that continued denial of the benefits is no

longer in the public interest.”

Read the Full Study Below:

Sound Moderators on Firearms in New South Wales

Correction: The statement at 1:30 in this video should be “… murdered by a firearm when they are just as likely to be injured by lightning.”

In this video Rod Giltaca discusses the statistical reality of the number of Canadians that are licenced to own guns, the number of gun related homicides, and the number of gun related accidental deaths in Canada and touches on how the real numbers are far fewer then often portrayed in the Canadian Media.

Supporting Information

Number of Gun Owners:

The 2015 Commissioner of Firearms Report lists the number of individual licenced gun owners in Canada at 2,026,011 individuals. The number 2.1 million quoted in the video is a projection based on a continuation of the historical increase since the last published data at the end of 2015.

The full report can be found here. 2015 Commissioner of Firearms Report

Dr. Gary A. Mauser is a Canadian criminologist and emeritus professor in the Beedie School of Business at Simon Fraser University. He has done extensive research into gun control and firearms law in Canada. The actual number of gun owners in Canada is impossible to know, however his best estimate of the number of Canadians in peaceful possession of firearms in Canada is approximately 3 million.

Number of Homicides:

Statistics Canada tracks annual homicides by method in Canada. A summery of their data is below showing rates between 2011 and 2015:

| Homicides by method | |||||

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| homicides | |||||

| All methods | 605 | 548 | 509 | 521 | 604 |

| Shooting | 159 | 171 | 134 | 155 | 178 |

| Stabbing | 207 | 164 | 195 | 189 | 214 |

| Beating | 128 | 115 | 102 | 100 | 132 |

| Strangulation | 40 | 44 | 45 | 32 | 38 |

| Fire (burns/suffocation) | 22 | 17 | 5 | 7 | 8 |

| Other methods1 | 33 | 21 | 18 | 23 | 14 |

| Not known | 16 | 16 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| Notes: Homicide includes Criminal Code offences of murder, manslaughter and infanticide. If multiple methods against one victim are used, only the leading method causing the death is counted. Thus, only one method is scored per victim. 1. Other methods include poisoning, exposure, shaken baby syndrome, deaths caused by vehicles and heart attacks. Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM, table 253-0002 and Homicide Survey, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. Last modified: 2016-11-23. |

|||||

Lightning statistics:

Environment Canada tracks lightning related injuries and deaths in Canada. Detailed statistics for the years 1986 – 2005 can be found here. https://www.ec.gc.ca/foudre-lightning/default.asp?lang=En&n=5D5FB4F8-1

Deaths and Medical Deaths:

Statistics Canada tracks annual deaths in Canada. Below is a summary of their data on total deaths between 2011 and 2016.

| Deaths, estimates, by province and territory | |||||

| 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | |

| number | |||||

| Canada | 241,500 | 250,407 | 254,855 | 266,164 | 269,012 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 4,634 | 4,701 | 4,821 | 4,943 | 5,069 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1,247 | 1,245 | 1,271 | 1,296 | 1,321 |

| Nova Scotia | 8,349 | 8,509 | 8,684 | 8,854 | 9,036 |

| New Brunswick | 6,332 | 6,536 | 6,708 | 6,870 | 7,036 |

| Quebec | 58,941 | 61,642 | 60,850 | 65,550 | 62,650 |

| Ontario | 88,466 | 92,472 | 95,894 | 99,231 | 102,701 |

| Manitoba | 10,086 | 10,158 | 10,338 | 10,503 | 10,676 |

| Saskatchewan | 9,095 | 9,265 | 9,381 | 9,482 | 9,577 |

| Alberta | 21,531 | 22,441 | 23,321 | 24,164 | 24,980 |

| British Columbia | 32,253 | 32,859 | 32,989 | 34,652 | 35,325 |

| Yukon | 215 | 211 | 217 | 226 | 234 |

| Northwest Territories | 189 | 205 | 213 | 222 | 233 |

| Nunavut | 162 | 163 | 168 | 171 | 174 |

| Notes: Period from July 1 to June 30. The numbers for deaths are final up to 2012/2013, updated for 2013/2014 and 2014/2015 and preliminary for 2015/2016. Preliminary and updated estimates of deaths were produced by Demography Division, Statistics Canada. Final data were produced by Health Statistics Division, Statistics Canada. However, the final estimates included in this table may differ from the data released by the Health Statistics Division, due to distribution of unknown province. Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM, table 051-0004 and Catalogue no. 91-215-X. Last modified: 2016-09-28. |

|||||

The Globe and Mail published a story in June 2016 estimating the number of deaths due to preventable medical errors to be up to 24,000 per year. Other stories published in previous years estimate that number might be even higher. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health-and-fitness/health/toronto-hospitals-embark-on-safety-initiative-to-prevent-medical-error-deaths/article30610569/

In this video Rod Giltaca, President of the Canadian Coalition for Firearm Rights, discusses the number of firearms owned by legal gun owners in Canada. He reviews the requirements and process one goes through to become licensed to own firearms, and describes in detail the extreme vetting process involved in doing so.

Supporting Information:

14 - 21 Million Firearms in Canada

This estimate comes from a large number of various sources in previous years. The last number from the full gun registry before it was destroyed was about 7.5 million registered guns. Some estimates for non-compliance of the registry were placed as high as 50%. There have also been estimates based on historical import records that factor into our estimate. Allister Muir, a spokesman for the Canadian Unlicensed Firearms Owners Association, estimated in 2012 that there are between 14 and 21 million guns in Canada, registered or otherwise.

http://news.nationalpost.com/news/canada/more-guns-in-canada-this-year-but-fewer-owners-rcmp

2.1 Million PAL holders in Canada:

The 2015 Commissioner of Firearms Report lists the number of individual licensed gun owners in Canada at 2,026,011 individuals. The number 2.1 million quoted in the video is a projection based on a continuation of the historical increase since the last published data at the end of 2015.

The full report can be found here. 2015 Commissioner of Firearms Report

Mandatory Safety Course:

It's important to note that an additional requirement not mentioned specifically in this video is mandatory participation in the Canadian Firearms Safety Course and associated testing. The content of this course is controlled and approved by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Canadian Firearms Program and was developed to meet the mandatory requirements of section 7 of the Firearms Act.To be eligible to apply for a Possession and Acquisition Licence, classroom participation in the full CFSC is mandatory for first-time licence applicants. Once the course is completed, individuals then must pass the tests.

Topics covered in the CFSC include:

http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/cfp-pcaf/safe_sur/cour-eng.htm

Licence Application Requirements:

Processing a firearms licence application involves a variety of background checks. In some cases, in-depth investigations are conducted. The RCMP requires a minimum of 45 days to process an application. There is a legislated minimum 28-day waiting period for all applicants who do not presently hold a valid firearms licence. A PAL is valid for a period of five 5 years

A 5 year personal history must be provided by all applicants. The personal history includes all information pertaining to criminal charges and convictions, peace bonds and protection orders, history of suicidal tendencies, depression, substance and alcohol abuse, behavioral problems, emotional problems, reports to police or social services about the applicant regarding violence or threats of violence or domestic conflicts. An applicant is also required to declare any divorce, separation, breakdown of a relationship, job loss, or bankruptcy. All applicants must also provide contact information for any spouse or common-law partner and every conjugal partner in the previous 2 years. In addition to the above requirements, 2 personal references must be provided to be interviewed by the RCMP as part of the background check.

Non-Residents and New Canadian Residents of less than 5 years must obtain a letter of good conduct issued by the local or state police of their current or previous country of residence.

A copy of the application can be found here: http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/cfp-pcaf/form-formulaire/pdfs/5592-eng.pdf

Police Check Every 24 Hours:

Continuous-eligibility screening is one of the most innovative features of the CFP. Rather than just doing background checks at the time of licensing and renewal (as was done under previous legislation), the CFRS is dynamic and continuously updated as new information comes to the attention of the police and courts concerning the behaviour of licence holders. All current holders of firearms licences, POL (Possession Only) and PAL (Possession and Acquisition of further firearms), are recorded in the Canadian Firearms Information System (CFIS). CFIS automatically checks with the Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) every day to determine whether a licence holder has been the subject of an incident report in CPIC. All matches generate a report entitled Firearms Interest Police (FIP) that is automatically forwarded to the CFO in the relevant province for follow-up. Some of these reports require no further action, but others may lead to review of the individual’s licence and may result in its revocation. . Continuous-eligibility screening reduces the likelihood that an individual who has shown they are a risk to public safety will be permitted to retain possession of firearms.

http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/pubs/fire-feu-eval/pg6-2-eng.htm

In this video Rod Giltaca, President of the Canadian Coalition for Firearm Rights, covers the significant increase in firearms regulations and laws in Canada that have been put into place since the early 1990s. It also highlights a selection of laws that lack any reasonable notion of common sense. Below you will find a brief history of legislation in Canada since 1991 as published by the RCMP, and references for each specific claim made in the video.

SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION

RCMP - History of Gun Control In Canada

1991-1994

Bill C-17 was introduced. It passed in the House of Commons on November 7, received Senate approval and Royal Assent on December 5, 1991, then came into force between 1992 and 1994. Changes to the FAC system included requiring applicants to provide a photograph and two references; imposing a mandatory 28-day waiting period for an FAC; a mandatory requirement for safety training; and expanding the application form to provide more background information. Bill C-17 also required a more detailed screening check of FAC applicants.

Some other major changes included: increased penalties for firearm-related crimes; new Criminal Code offences; new definitions for prohibited and restricted weapons; new regulations for firearms dealers; clearly defined regulations for the safe storage, handling and transportation of firearms; and a requirement that firearm regulations be drafted for review by Parliamentary committee before being made by Governor-in-Council. A major focus of the new legislation was the need for controls on military, para-military and high-firepower guns. New controls in this area included the prohibition of large-capacity cartridge magazines for automatic and semi-automatic firearms, the prohibition of automatic firearms that had been converted to avoid the 1978 prohibition (existing owners were exempted); and a series of Orders-in-Council prohibiting or restricting most para-military rifles and some types of non-sporting ammunition.

The Bill C-17 requirement for FAC applicants to show knowledge of the safe handling of firearms came into force in 1994. To demonstrate knowledge, applicants had to pass the test for a firearms safety course approved by a provincial Attorney General, or a firearms officer had to certify that the applicant was competent in handling firearms safely.

Bill C-17 added a requirement that safety courses had to cover firearms laws as well as safety issues.

After the 1993 federal election, the new Government indicated its intention to proceed with further controls, including some form of licensing and registration system that would apply to all firearms and their owners. Provincial and Federal officials met several times between January and July to define issues relating to universal licensing and registration proposals.

Between August 1994 and February 1995, policy options were defined for a new firearms control scheme, and new legislation was drafted.

1995

Bill C-68 was introduced on February 14. Senate approval and Royal Assent were granted on December 5, 1995. Major changes included:

Criminal Code amendments providing harsher penalties for certain serious crimes where firearms are used (e.g., kidnapping, murder);

the creation of the Firearms Act, to take the administrative and regulatory aspects of the licensing and registration system out of the Criminal Code;

a new licensing system to replace the FAC system; licences required to possess and acquire firearms, and to buy ammunition;

registration of all firearms, including shotguns and rifles.

The Chief Firearms Officer was tasked with issuing firearm licences, and the Firearms Registrar, registration certificates. The Registrar is responsible, among other things, for registering firearms owned by individuals and businesses.

Provision was also made in the Firearms Act for the appointment of ten Chief Firearms Officers, that is, one for each province, with some provinces also including a territory. Chief Firearms Officers can be appointed by the provincial or the federal government. Be they appointed federally or provincially, Chief Firearms Officers are responsible for such things as issuing, renewing, and revoking Possession and Acquisition Licences.

1996

The provisions requiring mandatory minimum sentences for serious firearms crimes came into effect in January. The Canada Firearms Centre (CFC) was given the task to develop the regulations, systems and infrastructure needed to implement the Firearms Act. CFC officials consulted extensively with the provinces and territories, and with groups and individuals with an interest in firearms, to ensure that the regulations reflected their needs as much as possible.

The Minister of Justice tabled proposed regulations on November 27. These dealt with such matters as:

- all fees payable under the Firearms Act;

- licensing requirements for firearms owners;

- safe storage, display and transportation requirements for individuals and businesses;

- authorizations to transport restricted or prohibited firearms;

- authorizations to carry restricted firearms and prohibited handguns for limited purposes;

- authorizations for businesses to import or export firearms;

- conditions for transferring firearms from one owner to another;

- record-keeping requirements for businesses;

- adaptations for Aboriginal people.

1997

In January and February, public hearings on the proposed regulations were held by the House of Commons Sub-Committee on the Draft Regulations on Firearms, of the Standing Committee of Justice and Legal Affairs, and by the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee. Based on the presentations that were made, a number of recommendations were made for improvements to the regulations. These recommendations were to clarify various provisions and to give more recognition to legitimate needs of firearms users. The Committee also recommended that the government develop a variety of communications programs to provide information on the new law to groups and individuals with an interest in firearms.

In April, the Minister of Justice tabled the government's response, accepting all but one of the Committee's 39 recommendations. The government rejected a recommendation for an additional procedure in the licence approval process.

In October, the Minister of Justice tabled some amendments to the 1996 regulations. She also tabled additional regulations at that time, dealing with:

- firearms registration certificates;

- exportation and importation of firearms;

- the operation of shooting clubs and shooting ranges;

- gun shows;

- special authority to possess; and

- public agents.

1998

The regulations were passed in March. The Firearms Act and regulations were scheduled to be phased in starting December 1, 1998. The Canadian Firearms Registry was transferred from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to the Department of Justice.

2001

As of January 1, 2001, Canadians needed a licence to possess and acquire firearms.

The National Weapons Enforcement Support Team (NWEST) was created to support law enforcement in combating the illegal movement of firearms. NWEST also assists police agencies in investigative support, training and lectures, analytical assistance, firearms tracing, expert witnesses, and links to a network of national and international firearms investigative groups.

2003

As of January 1, 2003, individuals needed a valid licence and registration certificate for all firearms in their possession, including non-restricted rifles and shotguns. Firearms businesses also required a valid business licence and registration certificate for all firearms in their inventory.

The Canada Firearms Centre was transferred from the Department of Justice on April 14, 2003, and became an independent agency within the Solicitor General Portfolio.

On May 13, 2003, Bill C-10A, An Act to Amend the Criminal Code (Firearms) and the Firearms Act received Royal Assent. Statutory authority of all operations was consolidated under the Canadian Firearms Commissioner, who reported directly to the Solicitor General, now known as the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada.

A Commissioner of Firearms, who has overall responsibility for the administration of the program, was appointed.

In June 2003, proposed amendments to the Regulations supporting the Firearms Act were tabled in Parliament. Consultations with key stakeholders concerning the proposed regulations took place in the fall of 2003.

2005

Some Bill C-10A regulations — those which improve service delivery, streamline processes and improve transparency and accountability — came into effect.

2006

Responsibility for the administration of the Firearms Act and the operation of the Canada Firearms Centre was transferred to the RCMP in May 2006. The Commissioner of the RCMP assumed the role of the Commissioner of Firearms.

In June, 2006, Bill C-21, An Act to Amend the Criminal Code and the Firearms Act, was tabled, with the intent of repealing the requirement to register non-restricted long guns. It dies on the order paper.

2007

Bill C-21 was reintroduced as Bill C-24.

2008

The RCMP amalgamated their firearms-related sections, the Canada Firearms Centre and the Firearms Support Services Directorate, into one integrated group, the Canadian Firearms Program (CFP).

Bill C-24, like its predecessor, Bill C-21, died on the order paper in September 2008.

The remainder of the Public Agents Firearms Regulations came into force on October 31, 2008. Police and other government agencies that use or hold firearms were required to report all firearms in their temporary or permanent possession.

2011

On October 25, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness introduced Bill C-19, An Act to amend the Criminal Code and the Firearms Act (Ending the Long-gun Registry Act).

2012

On April 5, Bill C-19, the Ending the Long-gun Registry Act, came into force. The bill amended the Criminal Code and the Firearms Act to remove the requirement to register non-restricted firearms, ordered the destruction of existing registration records and allowed the transferor of a non-restricted firearm to obtain confirmation of the validity of a transferee's firearms acquisition licence prior to the transfer being finalized.

Shortly after, the Government of Quebec filed a court challenge to Bill C-19. Due to a series of court orders and undertakings in these proceedings, non-restricted firearms registration records for the province of Quebec were retained, and Quebec residents continued to register non-restricted firearms.

In October, all non-restricted firearms registration records, except for Quebec, were destroyed.

2015

On March 27, the Supreme Court of Canada dismissed Quebec's appeal challenging the constitutionality of the provisions of the Ending the Long Gun Registry Act requiring destruction of the non-restricted registration records, and refused to order the transfer of these records to the Province of Quebec. As a result, the Canadian Firearms Program stopped accepting and processing registration/transfer applications for non-restricted firearms from within the province of Quebec, and all electronic records identified as being related to the non-restricted firearms registration records in Quebec were deleted.

On June 18, Bill C-42,the Common Sense Firearms Licensing Act, received royal assent, and the following provisions of that Act came into force: The Act amended the Firearms Act and Criminal Code to make classroom participation in firearms safety courses mandatory for first-time licence applicants; provide for the discretionary authority of Chief Firearms Officers to be subject to the regulations; strengthen the Criminal Code provisions relating to orders prohibiting the possession of firearms where a person is convicted of an offence involving domestic violence; and, provide the Governor in Council with the authority to prescribe firearms to be non-restricted or restricted.

On September 2, two additional provisions of the Common Sense Firearms Licensing Act came into force: the elimination of the Possession Only Licence (POL) and conversion of all existing POLs to Possession and Acquisition Licences; and the Authorization to Transport becoming a condition of a licence for certain routine and lawful activities. Other provisions of the Act which create a six month grace period at the end of a five year licence, and permitting the sharing of firearms import information when restricted and prohibited firearms are imported into Canada by businesses, are not yet in force.

http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/cfp-pcaf/pol-leg/hist/con-eng.htm

Rifle Banned Due to Appearance Alone:

In 2015 the RCMP Classified a version of the Mossberg Blaze, a rimfire 22 Long Rifle semi-automatic rifle, prohibited solely due to it’s resemblance to an AK 47. Other versions of this rifle from mossberg are all non-restricted in Canada.

Rifle Banned Due to Engravings:

In 2016, the RCMP classified classified a batch of newly imported CZ 858 Spartan rifles as prohibited based on some new engravings, which changed nothing as far as the rifles functionality. CZ 858 rifles that were already in Canada prior to this import are all currently non-restricted or restricted depending on barrel length.

https://firearmrights.ca/en/rcmp-prohibit-cz-858-spartan-rifle/

Shotgun Barrel Length - Same Gun, Different Classification:

A pump action shotgun who’s barrel is shortened by a gunsmith becomes prohibited:

Prohibited firearm* means:

But, a pump action shotgun purchased with the same short barrel from the factory would be non restricted:

Non-restricted firearm: any rifle or shotgun that is neither restricted nor prohibited.

Restricted firearm* means:

http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/cfp-pcaf/fs-fd/clas-eng.htm

Legal to target shoot with a large rifle on a large property, but not a handgun:

A Handgun may only be possessed inside the dwelling of the registered owner or at a shooting range approved by the chief firearms officer in each province. Authorizations to transport a handgun out of a dwelling and onto a registered owner's rural property for the purpose of target practice are not issued. The same restrictions do not apply to firearms classified as non-restricted.

Firearms Act - Section 17

Places where prohibited and restricted firearms may be possessed

17 Subject to sections 19 and 20, a prohibited firearm or restricted firearm, the holder of the registration certificate for which is an individual, may be possessed only at the dwelling-house of the individual, as recorded in the Canadian Firearms Registry, or at a place authorized by a chief firearms officer.

http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/F-11.6/page-4.html?wbdisable=true

Replica Firearms are Prohibited in Canada

To be prohibited as a replica firearm, a device must closely resemble an existing make and model of firearm.

http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/cfp-pcaf/fs-fd/replica-replique-eng.htm